Country research: Namibia

Homepage " Country research " Africa " Namibia

Namibia

Subpages:

(No subpages yet)

The content reflects the results of Perplexity's research and analysis and does not represent an expression of opinion by Gradido. They are intended to provide information and stimulate further discussion.

Namibia - Comprehensive research dossier for the Gradido project

The Republic of Namibia is at a critical turning point in its economic and social development. Despite political stability and democratic structures since independence in 1990, the country is struggling with structural challenges that make innovative solutions such as the Gradido system particularly relevant. This analysis systematically examines the potentials and hurdles for the introduction of a public welfare-oriented economic system in Namibia based on current data and social developments.

Economic and social starting position

Current economic performance and challenges

Namibia's economy recorded growth of 3.7 percent in 2024, with a slowdown to 3.1 percent forecast for 2025. This development reflects structural weaknesses that are exacerbated by external shocks. The primary sectors are particularly affected: agriculture contracted by 20.1% in the first quarter of 2025, mainly due to the lingering effects of the 2024 drought and outbreaks of lumpy skin disease in cattle.^1^3^5

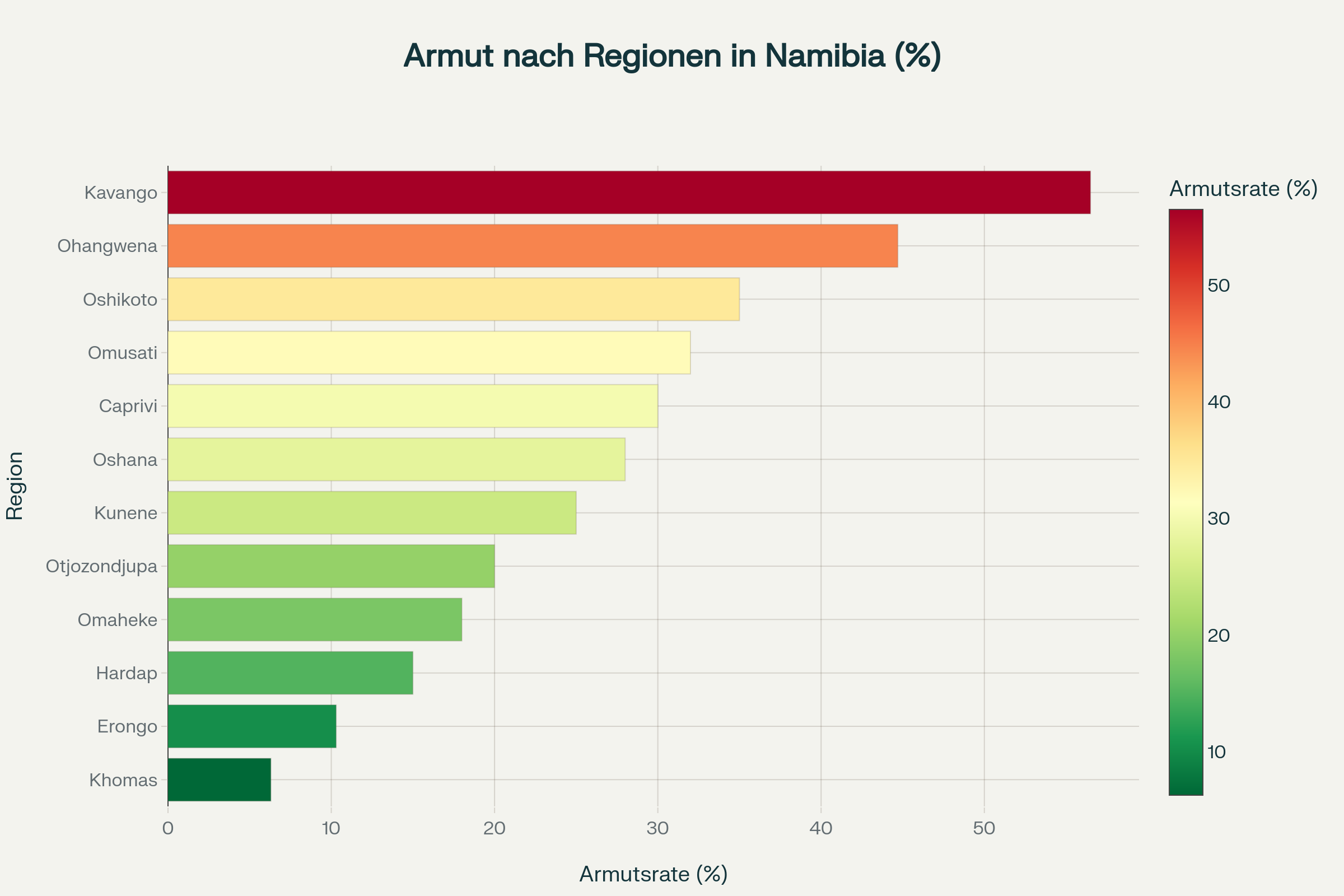

Regional distribution of poverty in Namibia - shows clear differences between northern and southern regions

The mining sector, traditionally an important economic sector, is struggling with declining diamond production due to weak global demand and competition from laboratory-grown alternatives. These developments highlight the vulnerability of a commodity-dependent economy and underline the need for economic diversification.^1

Labor market and employment crisis

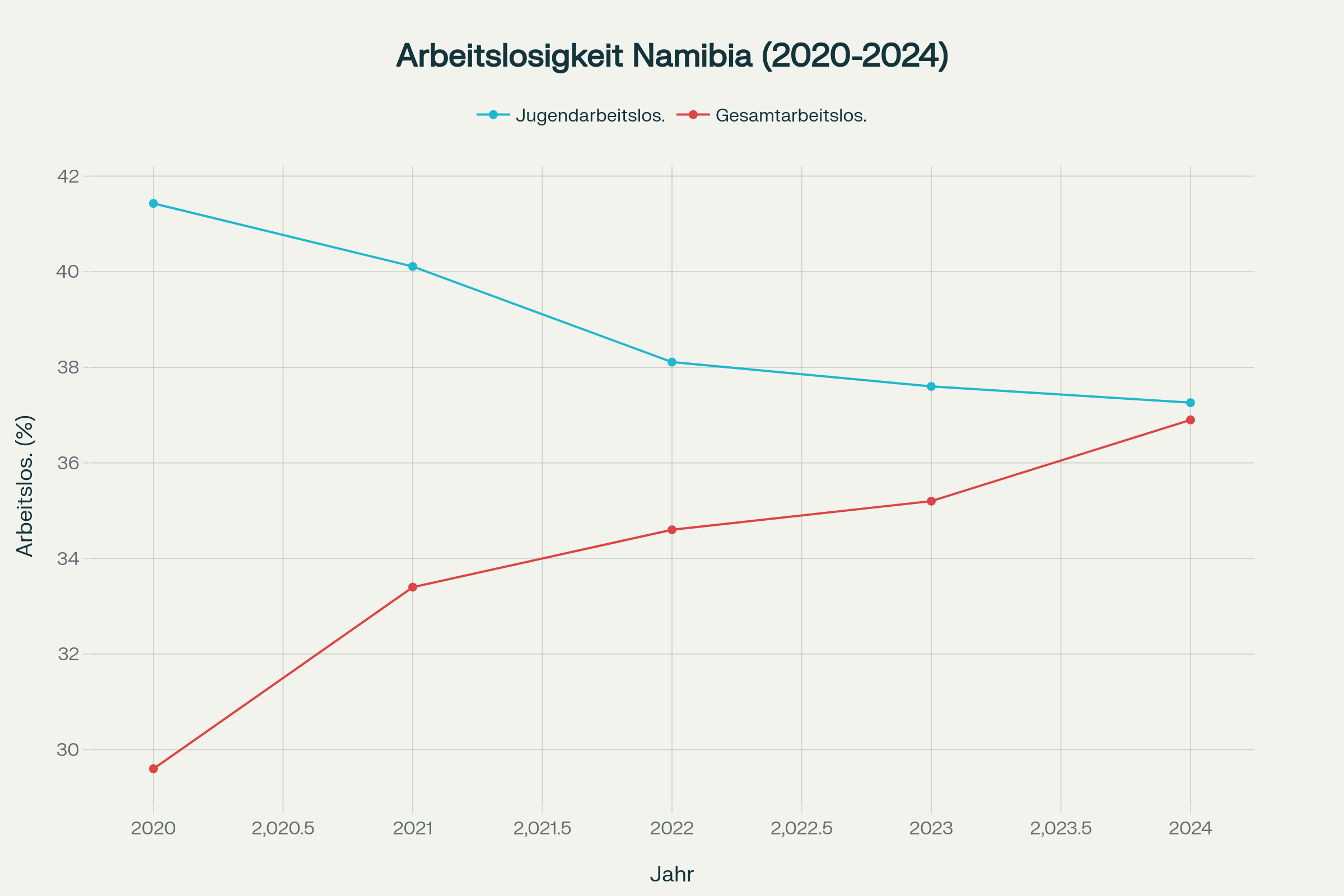

Unemployment trends in Namibia - youth unemployment remains consistently high

Unemployment is one of the most serious social challenges. With an overall unemployment rate of 36.9 percent, Namibia is well above the sub-Saharan average of 7.4 percent. Particularly alarming is the youth unemployment rate of 37.26% among 15 to 24-year-olds, which, although slightly declining, is still more than twice the global average.^2^8^10

This structural unemployment has far-reaching social consequences. Many young people see no prospects in their home regions and are migrating to urban areas, which is exacerbating demographic change and urbanization. The inadequate employment situation also contributes to political dissatisfaction, as shown by the weaker election results of the ruling SWAPO party in 2024.^11^13^15

Inequality and poverty distribution

Extreme inequality as a social challenge

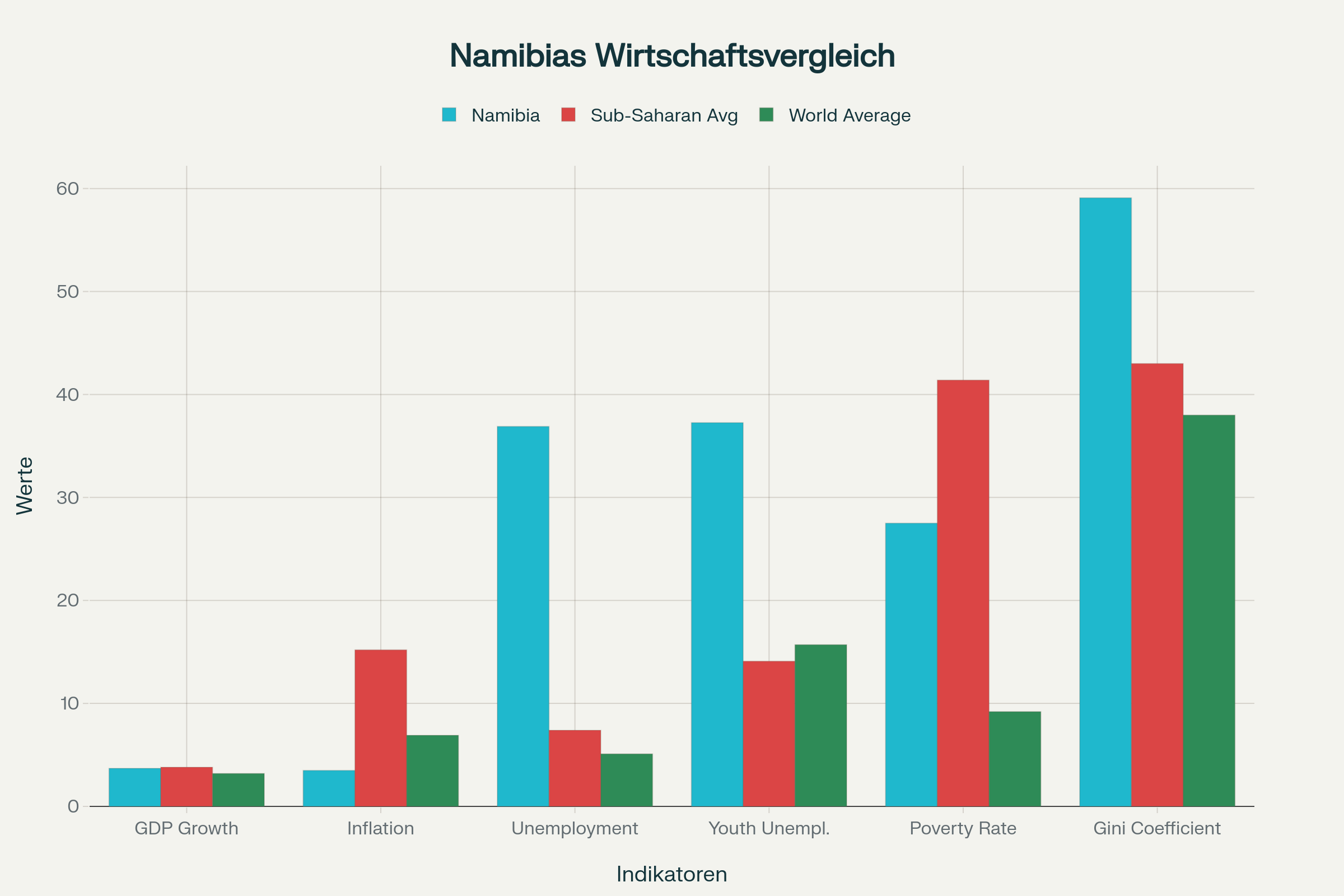

Comparison of Namibia's economic indicators with regional and global averages

With a Gini coefficient* of 59.1, Namibia has one of the highest inequality rates in the world - surpassed only by South Africa. This extreme inequality is the legacy of the apartheid era and is reflected in various dimensions: geographically between urban and rural areas, ethnically between different population groups and generationally between old and young.^17^18

Despite its status as an upper middle-income country, 40.6 percent of Namibians live in multidimensional poverty. The regional distribution shows extreme disparities: While only 6.3 percent of the population in Khomas (Windhoek) is poor, the poverty rate in Kavango is 56.5 percent. Together, the northern regions of Kavango and Ohangwena are home to over a third of all poor households in the country.^2^20^17

*The Gini coefficient or Gini index is a statistical measure of unequal distribution within a group that was developed by the Italian statistician Corrado Gini. The coefficient has values between 0 and 1; 0 corresponds to a completely equal distribution, 1 or 100 % corresponds to a complete concentration of one person in the group

Gender and intergenerational justice

The inequality also manifests itself in gender and age-specific differences. Women are disproportionately affected by unemployment, even though they make up 51.27 percent of the population. Traditional gender roles often limit their economic participation, while unpaid care work is not recognized by society. Young people between the ages of 15 and 34 make up 33.7 percent of the population, but have limited prospects for the future.^10

Labor migration and social mobility

Patterns of internal migration

Namibia has experienced a continuing rural exodus since independence. The degree of urbanization rose from 27 percent in 1991 to 49.5 percent in 2024. The Khomas and Erongo regions in particular are experiencing strong net migration, while rural areas are losing population.^14^10

These migration movements follow economic incentives: people move to where jobs are available. Over 40 percent of the inhabitants of Khomas and Erongo were born outside these regions. However, migration often leads to informal settlements and exacerbates urban problems.^14

Seasonality and precarious employment

A significant proportion of the population is in precarious employment. 55.8 percent of the workforce works in the informal sector, often without social security. Agriculture, which accounts for 31% of the workforce, is highly seasonal and at risk from climate change.^24^5

Governance and corruption

Political stability and democratic institutions

Ceremonial event in Namibia showcasing traditional dress and cultural heritage alongside formal national representation.

Namibia is considered a stable democracy with functioning institutions. The country ranks 22nd in the world for press freedom - the best score in Africa. The judiciary is largely independent and human rights are generally respected.^25^27

However, cracks are appearing in the political landscape. The SWAPO party, which has been in power since independence, lost its two-thirds majority for the first time in 2024 and now only holds 51 of 96 parliamentary seats. This reflects growing dissatisfaction, especially among young voters.^11

Corruption as a systemic problem

With a corruption index of 49 out of 100 points, Namibia ranks 59th out of 180 countries. Two thirds of Namibians see corruption as a growing problem. Public procurement is particularly problematic, where state-owned companies are often given preferential treatment.^28^29^31

The "Fishrot scandal" of 2019, in which government officials received millions in bribes for fishing quotas, shook confidence in the government. Although legal frameworks against corruption exist, enforcement is inconsistent.^13

Cultural strengths and community structures

Ethnic diversity as social capital

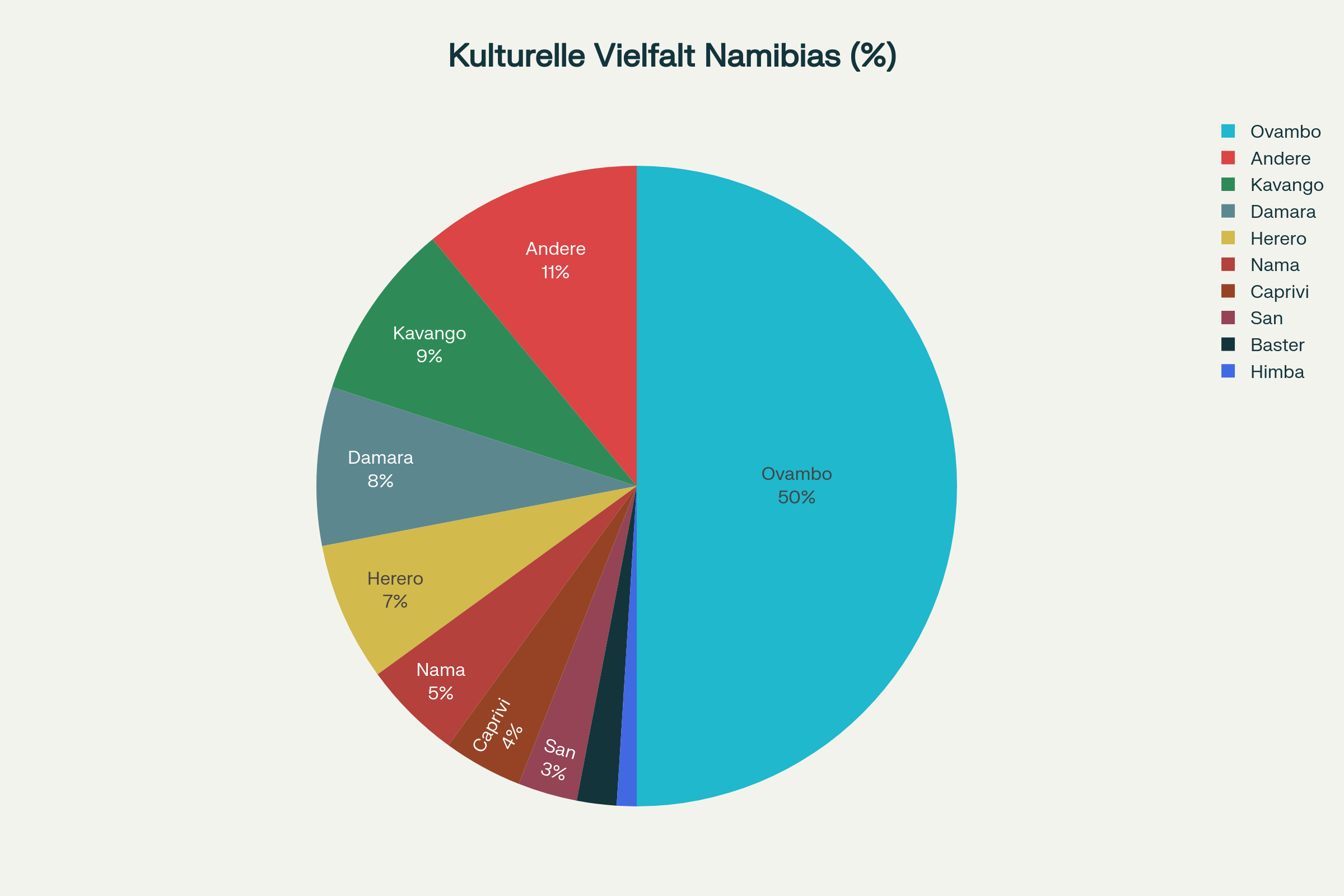

Ethnic composition of the Namibian population - Ovambo as the largest group

Namibia's cultural diversity represents both a challenge and an opportunity. The Ovambo are the largest ethnic group with 50 percent, followed by the Kavango (9 percent), Damara (8 percent) and Herero (7 percent). Each group has its own traditions, languages and social structures.^32^34

Himba women in traditional dress and ochre body paint participating in a cultural activity in Namibia.

This diversity manifests itself in strong community ties. Traditional kinship systems function as informal safety nets, especially in rural areas. Families are often extended families that provide mutual support. Many households are not nuclear families, but include other relatives.^36

Traditional values and modern challenges

Namibian society is characterized by values such as Ubuntu (humanity), community responsibility and respect for the elderly. These values are reflected in practical assistance: Children often live with relatives when parents have to work or when better educational opportunities present themselves.^33^36

Religiosity plays an important role, with Christianity dominating but traditional belief systems persisting. Ancestor worship and animistic practices often complement Christian beliefs.^34

Education and training

Education system between progress and challenges

The World Bank criticizes Namibia's education system as inadequate despite considerable investments of 18.5 billion Namibian dollars* annually. Fundamental problems include unequal access, low learning progress, inadequate infrastructure and a lack of teacher training.^37

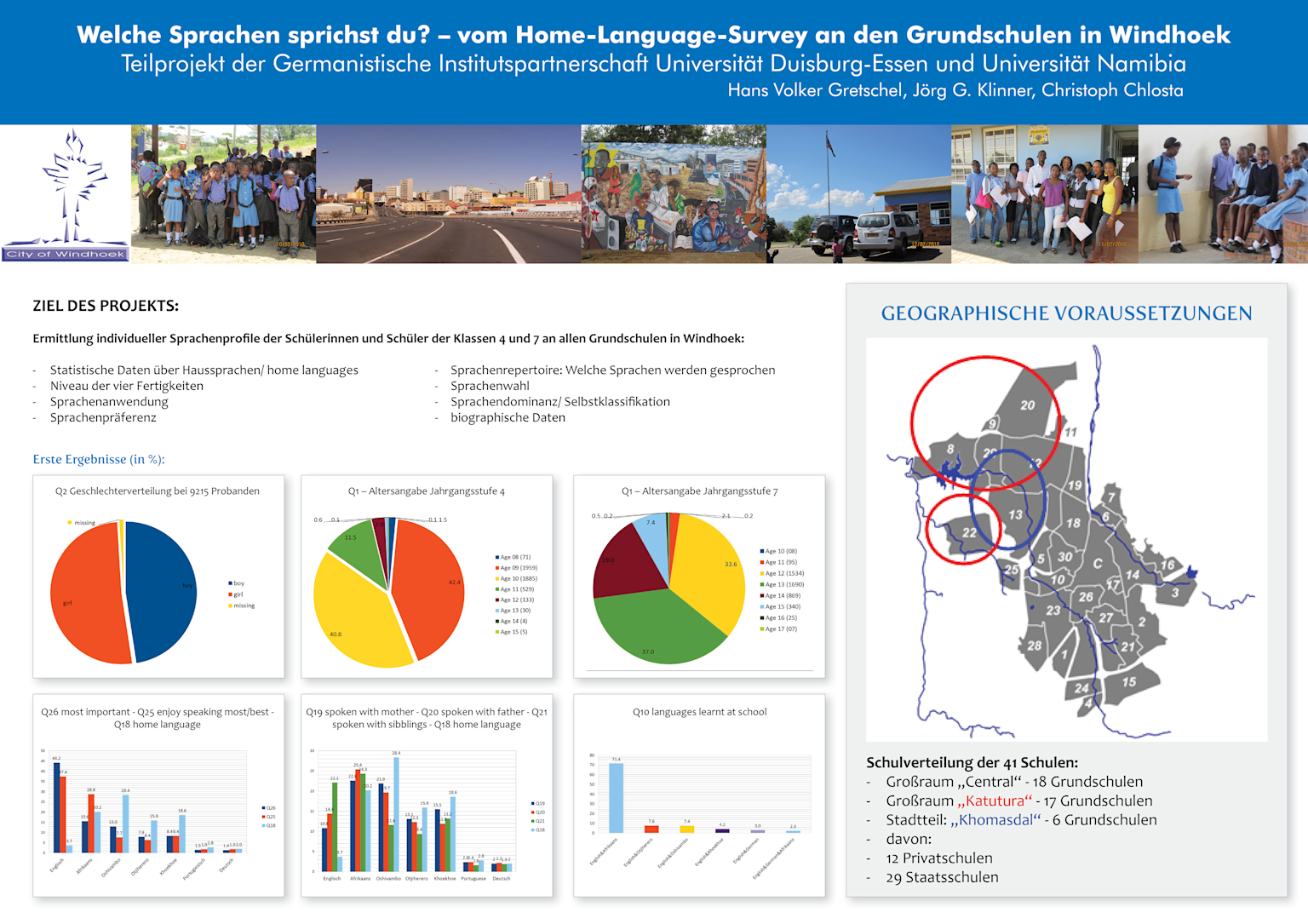

Children from socially disadvantaged families and remote regions are particularly disadvantaged. The diversity of languages makes education even more difficult: over 15 different native languages are spoken in Windhoek's elementary school.^39

*1 Namibian dollar corresponds to 0.05 EUR

Language use and school distribution survey among primary school students in Windhoek, Namibia showing linguistic diversity and demographic data.

Vocational training and skills development

The technical and vocational education and training (TVET) system is underdeveloped. Germany supports reforms in this area, but the demand for qualified workers exceeds the supply. This contributes to the high level of youth unemployment.^40

Healthcare and social security

Two-tier healthcare system

Namibia has a two-tier health system: an underfunded public sector and an expensive private sector. The Ministry of Health and Social Services received a budget of 11.3 billion Namibian dollars in 2024/25, yet staff shortages and unequal access remain key problems.^37^42

Medical care is particularly inadequate in rural areas. The school health program, introduced in 1990, is proving successful, but implementation varies greatly from region to region.^43

Social safety nets

Namibia has a relatively developed social security system, including old-age pensions. However, these are often insufficient to lift households out of poverty, as several people often have to live on one pension. The extended family system acts as an important informal safety net.^19

Volunteering and local initiatives

Cooperatives and self-help groups

Signboard at Mutjimangumwe Woodwork Cooperative supported by Namibia's NILALEG project with GEF and UNDP funding.

Namibia has around 135 registered cooperatives in various sectors: Agriculture, crafts, mining and services. These cooperatives create local jobs and strengthen communities. One example is seed multiplication, where cooperative members earn between 10,000 and 30,000 Namibian dollars (EUR 500 - 1,500) annually.^44

Challenges include transportation shortages, debt recovery and limited management capacity. Nevertheless, these initiatives demonstrate the potential of community-based economic models.^44

Traditional support systems

Informal support networks are particularly strong in rural areas. Neighborhood help, community work and barter systems function parallel to the formal economy. These structures could serve as the basis for alternative currency systems such as Gradido.^36

Openness to innovation and alternative economic models

Digitalization and technological infrastructure

Namibia is remarkably open to technological innovation. Internet penetration is high and digital payment systems are spreading rapidly. Mobile banking is increasingly being used. The government is actively promoting the digitalization of public services.^45

Sustainability awareness

Awareness of sustainability is growing, especially in the context of climate change. Namibia is developing ambitious plans for green hydrogen and renewable energy. This orientation towards sustainable development creates space for innovative economic models.^2

Regional differences in the willingness to innovate

Urban areas, especially Windhoek, are more open to new technologies and business models. Rural areas are more conservative, but are willing to experiment if solutions offer practical advantages. Cultural diversity means that innovations need to be introduced in a culturally sensitive way.

Aerial view of Windhoek city center showing modern buildings and historic architecture under a clear sky.

Aerial view of Windhoek city center highlighting the blend of historic and modern architecture.

Existing alternative economic models

Community-funded projects

Namibia has limited experience with alternative currency systems, but strong traditions of community financing. Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs) are common in many communities. These informal savings systems show that alternative financial structures are accepted.^44

Barter systems and the informal economy

Informal barter systems exist in rural areas, especially for agricultural products and services. These systems function on the basis of trust and show the potential for expanded alternative currencies.^36

Agriculture and food sovereignty

Climatic challenges

In 2024, Namibia experienced the worst drought in a century, which led to a national emergency. Wheat and maize production slumped by 83.7% and 51.8% respectively. This crisis illustrates the vulnerability of the agricultural sector to climate variability.^4

Over 70 percent of the population is directly or indirectly dependent on agriculture. Most of the farms are small-scale and practice subsistence farming with millet (mahangu), maize and sorghum as the main crops.^24

Production methods and sustainability

Traditional agriculture dominates, but there is growing interest in sustainable practices. Drip irrigation and solar water pumps are slowly spreading. Permaculture systems and organic farming are gaining attention, but are not yet widespread.^24

Cooperative agriculture

Agricultural cooperatives play an important role in access to inputs, equipment and markets. Joint ownership of machinery and collective purchasing of seeds and fertilizers help smallholder farms to reduce costs.^44

International actors and development cooperation

European Union and Germany

The EU is an important partner of Namibia with a Multi-Annual Indicative Program 2021-2027 focusing on education, green growth and good governance. Germany is the largest bilateral donor with over 20 projects through GIZ.^46^47

German cooperation focuses on sustainable economic development, natural resource management and inclusive urban development. The partnership builds on historical connections and shared values.^40

United Nations and multilateral organizations

The UN organizations are active in various areas, from health (WHO) to the environment (UNDP). The Global Environment Facility (GEF) supports projects for landscape restoration and poverty reduction.^43

The World Bank identifies education and health as priority areas and criticizes the low efficiency of public spending. The IMF emphasizes the need for structural reforms to diversify the economy.^48

Regional integration

As a member of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU), Namibia is integrated into regional economic structures. However, declining SACU revenues are a burden on the national budget. Integration into regional value chains remains limited.^1^3

Potential and hurdles for Gradido

Cultural and social conditions

Namibia's society has several characteristics that are favorable for Gradido. The strong community structures and traditions of mutual aid create a natural basis for a monetary system oriented towards the common good. The values of the Ubuntu philosophy - humanity, cohesion and shared responsibility - correspond to the basic principles of Gradido.^36^50

High youth unemployment and precarious employment create a need for alternative income opportunities. Gradido's concept of recognizing unpaid work could particularly benefit women and young people, who are often excluded from the formal economy.^49^51

Technological infrastructure

The relatively good digital infrastructure and growing use of mobile payment systems create favorable conditions for digital currencies. Experience with mobile transfers (such as M-Pesa in other African countries) shows the acceptance of alternative payment systems.^52^53

Legal and political hurdles

The current monetary system with the Namibian dollar and its peg to the South African rand creates legal restrictions. Membership of the Common Monetary Area limits monetary autonomy. Introducing it as an official currency would require significant legal changes.^45

Economic challenges

The extreme inequality could represent both an opportunity and an obstacle. On the one hand, they create a need for inclusive solutions; on the other, established elites could offer resistance. Dependence on SACU revenues and commodity exports limits fiscal flexibility.^1^50

Pilot approaches for Gradido in Namibia

Geographical focus

Rural areas with strong traditional structures, such as the northern regions, could be suitable as pilot regions. Community values are still strongly anchored there and the need for alternative income opportunities is high.^20^50

Informal settlements in urban areas are other possible pilot locations. Here, people often live in precarious conditions and could benefit from community-based solutions.^40

Target groups and sectors

Cooperatives could act as natural partners as they are already practicing alternative forms of business. Women in care work and young people without formal employment would be priority target groups.^44^51

The education sector offers potential for Gradido Pilot by recognizing voluntary educational work. Environmental protection projects could be promoted through ecological bonuses.^50^46

Step-by-step introduction

A gradual approach seems promising, starting with local exchange systems and neighborhood help. These could develop into larger networks and integrate digital components.^54^51

Partnerships with existing organizations - NGOs, cooperatives, communities - would promote trust and acceptance. Educational programs would need to be culturally sensitive and translated into local languages.

Conclusion and recommendations

Namibia offers a unique constellation for innovative economic models such as Gradido. The combination of strong community traditions, pressing social challenges and openness to technological innovation creates favorable conditions. At the same time, legal restrictions, political realities and cultural sensitivities require a cautious approach.

The greatest opportunities lie in addressing structural unemployment, recognizing unpaid work and strengthening local economic cycles. Gradido could have a particularly transformative effect in rural areas and informal settlements.

Cultural sensitivity, gradual introduction and partnerships with established organizations are critical to success. Pilot projects should start in areas with strong community structures and expand organically. Only through respectful collaboration with local communities can Gradido realize its potential as a tool for social justice and sustainable development in Namibia.