Country research: Madagascar

Homepage " Country research " Africa " Madagascar

The content reflects the results of Perplexity's research and analysis and does not represent an expression of opinion by Gradido. They are intended to provide information and stimulate further discussion.

Madagascar, Gradido, Open Source & Fihavanana - Paths to prosperity and dignity for people and nature

Madagascar is at a decisive turning point. As one of the poorest countries in the world, with 90 percent of the population living below the international poverty line, the island also embodies enormous potential for transformation. The combination of deep-rooted community traditions (Fihavanana), increasing digital connectivity, emerging women's initiatives and innovative economic models could pave the way for sustainable development that serves both people and nature. This dossier sheds light on how the Gradido model of the „Triple Good“ could merge with Malagasy values and act as a catalyst for profound social transformation.^1

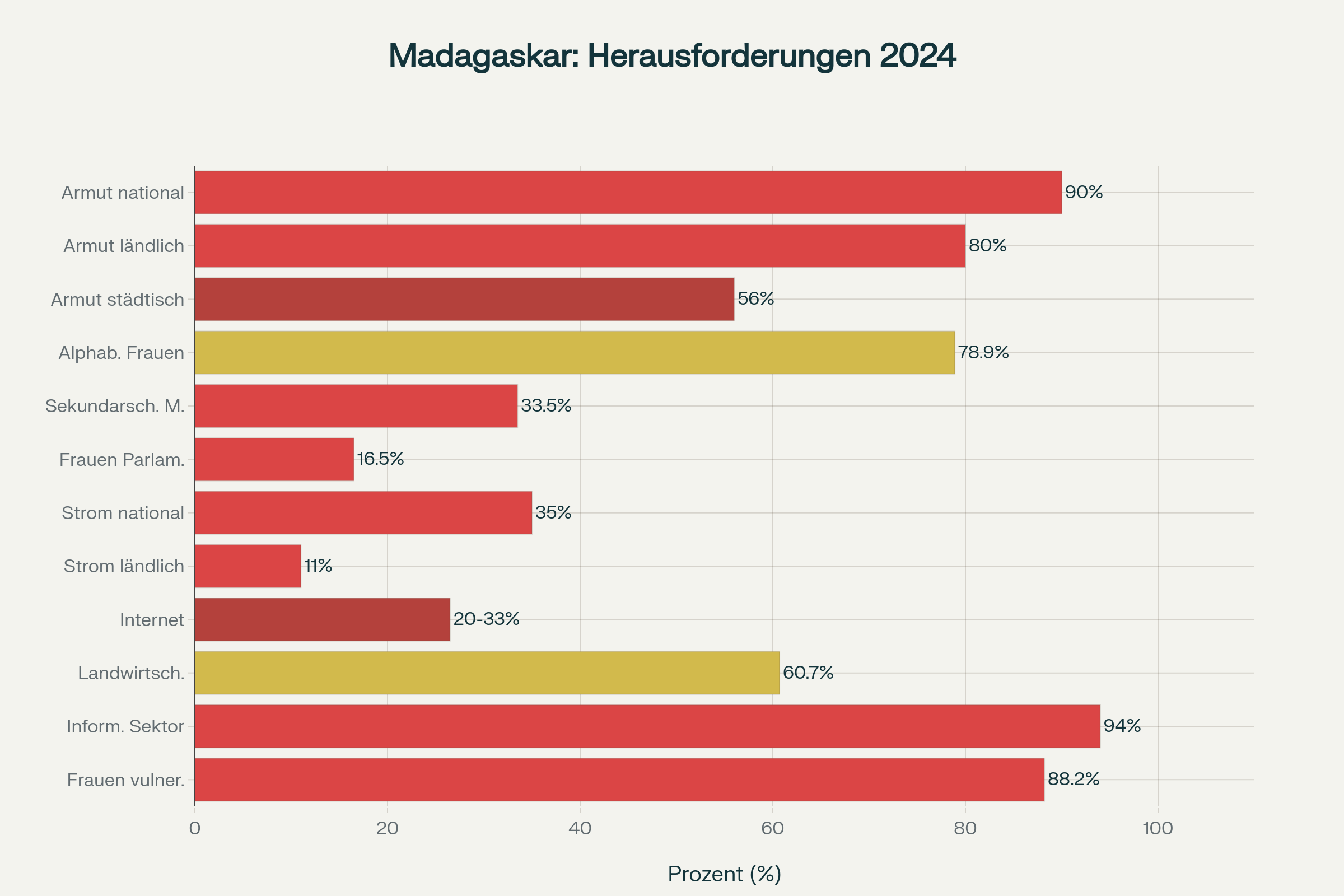

Madagascar faces enormous challenges: 90% of the population lives in poverty, only 11% of the rural population has access to electricity, and 94% work in the informal sector. At the same time, there is potential, such as the relatively high literacy rate among women.

Social, economic and political reality: a country in crisis mode

Extreme poverty as an omnipresent challenge

Madagascar's poverty statistics are staggering. Following a readjustment of the World Bank poverty line to 3 US dollars per day, people now live 28.76 million out of 31.96 million people - 90 percent of the population - in poverty. These figures do not represent abstract data, but individual fates: each of these people is a human being with names, memories, dreams and plans for the future who struggles to survive every day.^1

The distribution of poverty shows massive regional disparities. While in rural areas, where 80 percent of the population live, 79.9 percent live in poverty, the urban poverty rate is 56%**. The rapid increase in urban poverty is particularly alarming - it has risen by 31.5 percent in the last decade, especially in secondary cities, where the poverty rate has climbed from 46 to 61 percent. This development reflects the collapse of economic opportunities, a deteriorating business climate and a lack of investment in education, health and urban infrastructure.^3

The south of Madagascar is particularly affected. The region is experiencing its Fourth consecutive period of drought, which causes acute food insecurity and triggers massive migration flows to more fertile northern regions - which in turn leads to conflicts and additional pressure on land, forests and food systems.^4

Structural barriers and vicious circles

Madagascar's poverty is multidimensional and entrenched by structural barriers. 70 percent of the population are multidimensionally poor, experience deprivation in basic areas such as education, health and living conditions. Almost half of the population is food insecure, and children under the age of five suffer Almost every second child suffers from chronic malnutrition - one of the highest rates worldwide.^6^4

The employment structure reveals the poverty trap: 60.7 percent of all jobs are in agriculture, a sector with extremely low productivity. About 94 percent of the population work in the informal sector, without social security, stable income or legal protection. This massive informality reflects infrastructural bottlenecks, a lack of education and a business environment that does not create productive, formal jobs.^8

Political instability and elite capture

Political instability and a Capture by elites systematically inhibit development. „Elite capture“ means that progress, reforms and public investment are often steered or prevented by a few privileged groups for their own benefit - at the expense of the majority. Madagascar's state and political system primarily serve the elites, which is identified as a key obstacle to overcoming the country's fragility. The private sector faces a uneven playing field dominated by politically networked economic players. Corruption is pervasive, and a lack of transparency in regulatory decisions makes business activities more difficult.^9

Only 10.8 percent of GDP is collected as taxes, which massively restricts the government's capacity for public investment and service provision. This chronic underfunding of the state budget leads to basic infrastructure - roads, schools, health centers - falling into disrepair or not being built at all.^6

Fihavanana: Madagascar's Ubuntu and the power of community

The cultural DNA of solidarity

In the midst of these structural crises, there is a powerful cultural foundation: Fihavanana. This Malagasy concept encompasses the principles of solidarity, reciprocity and kinship and has been the cornerstone of social cohesion since pre-colonial times. Fihavanana is comparable to the South African concept of the Ubuntu („A person is a person through other people“), which emphasizes interdependence, mutual care and shared responsibility.^10^12

Fihavanana is based on three pillars: Respect, friendliness and reciprocity (mutuality). The concept begins at the family level, but extends to friends, neighbors, community members and even strangers. It structures the entire Malagasy social system horizontally and characterizes all the important transitional phases of life - birth, circumcision, marriage and death - during which everyone must be present and contribute to the ceremony in various ways (food, money, musical or dancing skills).^11

A Malagasy proverb illustrates the priority: „Better to lose a bit of money than a bit of friendship“. During COVID-19, the traditional values of solidarity and care were demonstrated through community actions that looked out for the most vulnerable.^11

Concrete practice: From Tana-maro to Valin-tanana

Fihavanana manifests itself in concrete collective solutions, especially among farmers, who make up 80 percent of the population. Traditional terms such as „Tana-maro“ and „Valin-tanana“ (mutual work) describe communal forms of work in agriculture. Malagasy proverbs such as „You can't dig soil under water unless you do it together“ reflect this practice.^11

Fihavanana serves as Highly effective social safety net. Networks of solidarity and reciprocity - based on kinship, community, religious or political affiliations - are vital for survival in poor communities facing overlapping food, climate and economic crises.^11

Limits and erosion of traditional values

Nevertheless, Fihavanana is eroding under the pressure of modernization, urbanization and economic hardship. Younger generations, especially in urban areas, are increasingly internalizing individualistic values. The subsistence economy, which traditionally required communal work, is giving way to market economy structures that encourage individual competition.^13

Fihavanana is also not free of ambivalence. The pursuit of social harmony can lead to Abuse and injustice are concealed, domestic violence against women and children for fear of disturbing the harmony of the family or community. A critical development is needed here that combines Fihavanana with universal human rights and gender justice.^12

Women and girls: the key to transformation

High employment rate with low recognition

Women play a central, but highly undervalued role in Madagascar's society and economy. The female labor force participation rate is an impressive 82.6 percent (2024), which is one of the highest in the world. Nevertheless 88.2 percent of women in vulnerable employment - without formal contracts, social security or adequate pay.^14

Structural barriers massively limit the economic contributions of women. They are Paid 37 percent less than men and are 20 percent more likely to be unemployed. Women are severely underrepresented in the political sphere: Only 16.5 percent of parliamentary seats, 37 percent of ministerial posts, 9 percent of governorships, 5 percent of mayorships and 7 percent of municipal and city councils are held by women (as of 2024).^15

Education as a bottleneck and lever

While the Literacy rate among adult women 78.9 percent and thus exceeds the regional average of 74.5 percent, only 33.5 percent of girls complete the first level of secondary school (compared to 30.3 percent of boys). This low completion rate drastically limits access to advanced skills, technical training and formal employment sectors.^14

A World Bank study shows that a one percentage point increase in female literacy is associated with an average increase in GDP per capita of 7.91 US dollar in Madagascar. Investments in girls' education also have demonstrable social dividends: They correlate with reduced infant mortality, better family health and lower birth rates.^14

But the hurdles are huge. Girls are often taken out of school to work at Housework, agricultural activities and care work to help. Early marriages and teenage pregnancies are the main reasons for dropping out of school. Gender-based violence in schools and a lack of freedom of choice exacerbate the situation.

Successful initiatives for girls' education

Promising projects demonstrate the potential of targeted interventions. Nofy i Androy („Dreams of Androy“) supports 700 rural girls with comprehensive educational services, including secondary and university fees, housing, school supplies and tutoring. The program also provides life skills training, body awareness education and leadership workshops that empower girls to combat harmful cultural norms such as child marriage and early pregnancy.^17

Passerelles Numériques Madagascar (PNM) offers a One-year post-secondary preparatory year in computer science with technical and soft skills training. The program is aimed at disadvantaged young people, whereby at least 50 percent young women should be. Since 2022, almost 530 persons benefit from the training, and 90 percent continue their studies at partner universities.^18

UNICEF's Let Us Learn Program, supported by Zonta International, achieved in the 2021-22 reporting period 1,200 children not enrolled in school (684 girls) with catch-up courses and built two classrooms. The program also offers Money transfers to vulnerable families who use „mothers“ guides" to start small businesses and send children to school.^19

Economic self-organization of women

At grassroots level, women organize themselves in Self-help groups (SHGs), to overcome economic vulnerability. The Caring Response Madagascar Foundation (CRMF) has since 2020 41 urban and rural SHGs with up to 12 women per group. In Toamasina are 340 female literacy graduates SHGs, and 300 of them achieved financial independence through textiles, agriculture, livestock farming, retail, food processing and hospitality.^20

The Stitch Sainte Luce-project has trained dozens of women in a rural village cluster in embroidery and business skills. The cooperative is now established and independent, with over 103 Women, which produce high-quality bags, purses and accessories. The income generated supports over 948 people in Sainte Luce through food, education, clothing or health care.^21

Environment, climate and agriculture: between crisis and regeneration

Deforestation and ecological collapse

Madagascar's unique biodiversity - for example 85 percent of the species are found nowhere else on earth - is under massive threat. Historically green regions with rich forests, such as Diana in the north, are now being destroyed by Deforestation, land degradation and climate change severely damaged.^5^23

The causes are complex. Demographic pressure has led to the local population Forests burned down to clear land for agriculture. They practiced monocultures that quickly depleted the soil, causing farmers to abandon their plots and repeat the cycle in neighboring areas. Trees were also planted for Illegal charcoal production burned to generate a quick income.^24

In the period 1973-2017, southern Madagascar recorded a 34 percent decline in forest cover. The degraded landscape and poor soils exacerbate the effects of climate change. Rainfall decreased and seasons became irregular, This led to further land degradation and declining crop yields - which in turn prompted farmers to turn to firewood production and destroy more forests.^25

Climate volatility and natural disasters

Madagascar is the fourth most vulnerable country in the world to climate change. Extreme weather events - An average of three cyclones per year, droughts and floods - cause death, displacement, destruction of homes, infrastructure and crops. The damage caused by four tropical storms in 2022 alone was equivalent to almost 5 percent of Madagascar's GDP.^26^22

The South has been experiencing a prolonged drought for four years, which has driven over a million people into hunger. This crisis is caused by Climate change and deforestation that create a dangerous vicious circle: Climate change threatens harvests and livelihoods, causing farmers to expand farms by cutting down trees - which in turn intensifies droughts, flooding and soil erosion.^22

Regenerative agriculture as a way out

Encouraging pilot projects show that regenerative agriculture can break this vicious circle. The Zanatany Rice System, co-developed by the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) with smallholder farmers, promotes nature-based solutions in crops, livestock and forestry that restore soil and water and improve biodiversity - while increasing yields.^27

Zanatany makes it possible for farmers, Sowing rice plants directly into the soil instead of transplanting seedlings from nurseries, which allows harvesting two to three weeks earlier. The system uses 80 percent less seed, reduces costs and labor, especially for women who usually manage nurseries and transplant seedlings.^27

About 116,000 people in Madagascar, more than half of them women, have been reached, and farmers save an average of 20 percent of their input costs. One farmer, Randriamitantsoa, reports: „The soil became more fertile as it absorbed more nutrients, and our yields increased.“ After stopping chemical inputs, his wife's health also improved. His income quadrupled from 500,000 ariary (USD 110) per year to this amount per quarter.^27

A project by Conservation International and the Green Climate Fund showed similar successes. Farmers who Climate-smart practices adopted - drought-resistant plants, mulching to prevent erosion, planting native fruit trees - were not only less likely to deforest surrounding land, but also had greater food security. The decline in food insecurity was visible surprisingly quickly.^22

Digitalization, open source and technological innovation

Digital divide and rapid growth

Madagascar's digital landscape is characterized by extreme inequality embossed. Only 20-33 percent of the population use the Internet (depending on the source), and about 80 percent of Madagascans do not use the Internet at all. In rural areas, only 29 percent of women have access to a cell phone, 2.6 percent to the Internet and 1.4 percent to a computer.^28^30

Nevertheless, there is rapid growth. The Mobile phone penetration increased between 2022 and 2023 by 79.47 percent. About 9.6 million mobile Internet subscribers were registered in 2023, compared to 4.9 million in the previous year. Mobile data consumption soared by 49.07 percent from 127,684 TB to 190,339 TB.^31

However, the costs are prohibitive. Monthly mobile internet expenditure in 2023 represented 6.28 percent of gross national income per capita - three times higher than the limit set by the ITU 2 percent affordability threshold. The government is now urging telecommunications providers to lower prices in order to promote digital inclusion.^29

An ambitious 24 million dollar program (DECIM) was launched in order to 664,000 connected digital devices to be distributed, of which 400,000 specifically for women and girls. The program aims to reduce technology access disparities and strengthen digital and economic inclusion.^28

Open source movement and technical talent

Madagascar has a Strong supply of software development talent, with about 500-600 qualified software engineers, who graduate every year. A dynamic Information and communication technology (ICT) private sector can be used to deliver digital services that are tailored to the needs of the population.^32

The Madagascar Open Source Community (MOSC) offers an online platform for sharing and learning about open source technologies. Madagascar has a National Open Source Strategy (SON) to promote the development and use of open source software and open standards.^34

Remarkable technologists like Henri Razafinarivo (founder of Smart Solutions, specializing in open source solutions), Toavina Ralambomahay (software developer and founder of FOSSFA, advocate of open data) and Mialy Andriamananjara (founder of Miray IT Solutions, member of the MOSC) are driving the open source movement forward.^34

Educational initiatives for digital skills

Several initiatives promote digital skills, especially for disadvantaged young people. Education for Madagascar's CARE program (Coding Applications Robotics Education) trains Malagasy children in programming. The project has Almost 40 devices, 3 video projectors, fiber optic network, hundreds of books and 2 trained teachers. „By learning programming, Malagasy children are preparing for a brighter future, as programming is one of the rare professions that does not necessarily require moving abroad,“ it says.^35

Onja, a social enterprise, trains talented young people in Madagascar in English and software development and places them in global tech careers. Tantely Andrianarivola, one of Onja's first graduates, had neither computer nor English skills, but became a front-end developer at 90POE in 2.5 years. „Onja aims to bring the Malagasy tech community together and create alternative career paths for those interested in software engineering in Madagascar,“ explains the initiative.^36

Microfinance, savings groups and alternative economic cycles

Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs)

Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs) have become a critical support network for small farmers. They often provide the only accessible means, to obtain production inputs such as seeds and equipment as well as household expenditure on education and health at affordable rates without collateral.^37

VSLAs in Madagascar represent more than just financial services - they strengthen social safety nets within communities. In Tanzania, the Tele-Bere VSL Association mobilized 150 VSL groups with over 4,500 members (over 85 percent women) and about GHS 2.6 million (approx. USD 450,000) in savings per year.^37

In Madagascar's Women's National Platform for Sustainable Development and Food Security (PNFDDSA) women use VSLA funds to develop business plans, support start-ups such as tree nurseries with loans and organize trade fairs.^37

A success story is Joséphine Rasoanantenaina from the village of PK7. Despite working two jobs, she only earned half the money she needed. After joining one of the organizations supported by Money for Madagascar Community savings group (GEC) her life was transformed. She explains: „Before, the inhabitants of my village had done ‚Voa mamy‘, but the approach was not similar to that of the GEC. The latter is more disciplined and formal.“ Through training in vegetable gardening, which she passed on, all members now have vegetable gardens for additional income.^38

Microfinance and digital financial solutions

Despite the diversity of existing financial institutions - banks, microfinance institutions (MFIs), financial institutions, e-money institutions - the Financial inclusion low and unevenly distributed. According to the FinScope Consumer Survey 2016, only 29 percent of Madagascan adults have access to formal financial services. Only 12 percent use a bank account, and 46 percent have no access at all - not even to informal financial services.^39

Socio-economic conditions, low literacy levels, infrastructural limitations (roads, network, connectivity, electricity) and an underdeveloped payment ecosystem make it difficult for formal financial service providers to reach vulnerable populations in rural areas.^39

As an alternative, since 2006 NGOs such as CARE International and Catholic Relief Services (CRS) the foundation of Savings groups for vulnerable, underserved and unserved people in rural areas. These were inspired by the Mata Masu Dubara model from Niger.^39

Première Agence de Microfinance (PAMF)-Madagascar, a depository and credit institution licensed by the central bank, aims to combat poverty through economic and social exclusion. 70 percent of its borrowers live in rural areas and use digital financial services. Together with the Grameen Foundation, PAMF developed the first Progress Out of Poverty (PPI) Scorecard for Madagascar, a widely used tool in microfinance for measuring poverty outreach.^40

Local currencies and complementary systems

While formal alternative or complementary currencies are not yet widely used in Madagascar, experience with digital wallets and Mobile Money a growing openness to innovative financial systems. This infrastructure could serve as a basis for the future introduction of complementary currency systems such as Gradido.^39

Gradido and Madagascar: a natural resonance

The threefold good and Fihavanana

The Gradido model of the „Natural Economy of Life“ is based on the fundamental ethical principle of „Triple well-being“the good of the individual, the good of the community and the good of the whole (environment and nature). This approach harmonizes exceptionally well with Madagascar's Fihavanana tradition, which also harmonizes the well-being of the individual with that of the community and the wider ecosystem.^11^42

Gradido proposes a triple creation of money before: For each person, monthly 3,000 Gradido (GDD) created - without creating debt. One third goes to each person as Active basic income, one third to the public budget for the provision of general infrastructure, and one third to a Compensation and environment fund, to eliminate economic and ecological legacies.^42

Active basic income: Unconditional participation

The Active basic income is the thanks of the community for the Unconditional participationEvery person has the right to contribute to the community according to their inclinations and abilities. The reward is 20 gradido per hour up to a maximum of 50 hours per month, so maximum 1,000 Gradido per month. People who are unable to contribute due to age or health receive their basic income unconditionally.^42^44

This concept could be applied in Madagascar transformative effect unfold. It would Massive unpaid care work by women, caring for children, the elderly and the sick as well as household work Making visible and appreciating. In addition traditional Fihavanana practices - mutual work, neighborhood help, community projects - are directly remunerated with Gradido, which would strengthen these essential social ties.^11^42

Environmental fund for regeneration

The Compensation and Environment Fund (AUF) could Madagascar's urgent environmental challenges address. One third of all money creation would be continuously invested in the Restoration and preservation of nature and the environment flow. This could finance the following initiatives:^42

Reforestation programs and restoration of degraded landscapes^5

Regenerative agricultural practices (Zanatany system, agroforestry)^27

Mangrove restoration and coastal protection^5

Solar electrification and renewable energy for rural communities^48^50

Biodiversity protection and sustainable use of natural resources^22

Since 85 percent of the population depend on agriculture as their main source of livelihood, a well-financed environmental fund would improve direct living conditions and at the same time protect Madagascar's unique natural heritage.^27

Tax-free community budget

The second third of money creation - 1,000 GDD per capita per month - flows into the public budget, which would be as large as it is currently in Germany, including healthcare and social benefits. As this is already done through money creation No taxes, compulsory insurance and other levies necessary.^43

For Madagascar, where only 10.8 percent of GDP is collected as taxes and the government is chronically underfunded, this would be revolutionary. A solid, tax-free budget could:^6

Schools, health centers and infrastructure build and maintain in rural areas^7^52

Free healthcare guarantee for all^53

Education up to secondary level without hidden costs[^15][^54]

Roads, bridges and market entrances for farmers^55

Monetary transience and stable system

Gradido sees a Monthly perishability (negative interest) of 5.6 percent which, together with the monthly money creation, forms a self-regulating system that Keeps money supply and prices stable. This prevents deflation or inflation and frees the economy from the constant pressure to grow.^43

Transience also promotes Investments in real assets - Education, infrastructure, sustainable products - instead of speculative hoarding. In an economy that is currently under Inflation of over 8 percent a stable currency system would create planning security for households and companies.^57

Pilot projects in Madagascar: concrete approaches

Ideal starting conditions

Madagascar offers exceptionally favorable conditions for Gradido pilot projects, which can be compared with similar conditions in other countries such as the Philippines, Greece and the Maldives:^58^59

Existing community structuresThe traditionally close-knit village communities with established neighborhood support systems (Fihavanana) provide an ideal basis for community-based currency systems.^11

Geographical isolation as an advantageThe natural demarcation of village communities, especially on offshore islands, could enable controlled pilot projects without destabilizing the national monetary system.^58

High digital readinessAdvanced digitalization and openness to blockchain technologies create the technical prerequisites for digital gradido implementation.^32^58

Need for diversificationThe economic dependence on subsistence farming and the high dependence on imports create demand for alternative economic models.^55

Care work integration: The existing system unpaid care work and Volunteering could be strengthened and made visible through gradido recognition.^45

Phase model for implementation

A step-by-step procedure could look like this:

Phase 1: Community-based pilot projects (6-12 months)

Selection of 3-5 rural village communities with strong Fihavanana practices and openness to innovation

Focus on existing Community projects such as health centers, schools, agricultural cooperatives or reforestation initiatives

Integration with traditional Neighborhood assistance systems and VSLAs

Partnership with local NGOs such as Ny Tanintsika, SEED Madagascar, Akamasoa or Mitsinjo Association^38^61

Phase 2: Sector-specific expansion (1-2 years)

Piloting in the Care sectorCare for the elderly, childcare, health services in villages

Cooperation with agricultural projects (Zanatany, agroforestry) and sustainable tourism initiatives^27^46

Integration of Educational institutions for awareness-raising and digital literacy^18

Special Women's initiativesStitch cooperatives, self-help groups, Nofy i Androy educational programs^20^17

Phase 3: Technological integration (2-3 years)

Development of Gradido Mobile Apps, adapted to local needs and languages (Malagasy, French)

Integration with existing digital infrastructure and mobile money systems

Use of Open source technology and integration of the Madagascar Open Source Community^34

Structure of Community servers with cross-community transactions^62

Phase 4: Institutional anchoring (3-5 years)

Cooperation with Municipal councils (Fokontany) for local governance integration

Cooperation with UN development programs (UNDP, UNICEF, FAO) and the World Bank

Development legal framework for complementary currencies

Partnership with the Ministry for Digital Development and the central bank for regulatory recognition^28

Concrete fields of application

Advancement of women and education

Gradido could Girls' education programs by remunerating the care work of mothers, mentors and teachers. „Mothers“ leaders", who are already central to cash transfer programs, could receive Gradido for community organizing and supporting vulnerable families.^19

Projects like Passerelles Numériques Madagascar could use Gradido to reward students for charitable contributions (tutoring for younger pupils, digital literacy in villages, open source project work).^18

Regenerative agriculture and the environment

Farmers who Zanatany principles or Agroforestry could be remunerated from the environmental fund. This would create incentives to switch from destructive slash-and-burn practices to regenerative methods.^27^47

Reforestation initiatives like the successful Ny Tanintsika project, which restored 47 hectares of forest in one year and planted 35,000 trees, could be scaled up through Gradido. Community members would be paid for tree nurseries, seed collection, planting and maintenance.^5

Solar electrification

WeLight Madagascarthat 120 village solar mini-grids built in order to 45,000 households and businesses sustainable access to energy could be scaled up with Gradido funding from the community budget.^48

The data provided by the Aga Khan Foundation and atmosfair trained 744 Women solar engineers, which until 2030 630,000 households could be remunerated by Gradido for installation, maintenance and training - giving women economic independence and technical skills.^50

Health and social services

Community Health Volunteers (CHVs), of which over 18,000 through the ACCESS program could receive gradido for health education, family planning, malaria management and nutrition monitoring.^51

Initiatives such as PluriElleswhich 25 Midwives recruited in community birthing centers in rural areas could be funded through the community budget so that Women's access to nearby healthcare without prohibitive travel costs.^64

Synergies, success factors and growth potential

Open Source, Grassroots and Gradido: What they can learn from each other

Open source principles - Transparency, collaborative development, open access - resonate deeply with Gradido values and Fihavanana. Madagascar's growing open source community could:^34

Technological infrastructure Develop for Gradido implementation (mobile apps, community server, blockchain integration)^62

Educational materials and create training modules in Malagasy and French

Participatory governance tools Develop a collaborative decision-making process for Gradido deployment

Grassroots women's initiatives such as self-help groups, stitch cooperatives and educational programs:

As first adopters and Multipliers serve for Gradido

Practical knowledge on community-based financing and collective decision-making

Culturally adapted communication strategies develop that emphasize Fihavanana values

Gradido could:

Existing initiatives with sustainable financing support that does not depend on external donors

Appreciation and visibility for unpaid care and community work

A Inclusive economic system that leaves no one behind

Critical success factors

1. cultural adaptation and awareness-raising

The introduction of Gradido requires a profound change in awareness - away from a scarcity mindset towards gratitude, cooperation and a focus on the common good. Comprehensive educational campaigns in collaboration with traditional leaders (Mpiadidy, Mpanandro), schools and community organizations are essential.^45

Fihavanana offers a natural starting pointGradido can be framed as a modern development of traditional values that strengthens these values rather than replacing them.^11

2. political support and legal framework

Long-term Political support is essential for the sustainable development of alternative currency systems. Close cooperation with the Ministry for Digital Developmentthe Central Bank, and progressive parliamentarians is needed to create a legal framework that allows complementary currencies alongside the ariary.^28^67

Pilot projects should be closely local authorities (fokontany chiefs, mayors) and the Agence pour le Développement de l'Électrification Rurale (ADER) cooperate in order to gain legitimacy and institutional support.^48

3. digital infrastructure and inclusion

While digital connectivity is growing, the digital divide a major obstacle, especially for Rural women. Gradido implementation must be used with digital literacy and Multiple access routes mobile apps for smartphone users, SMS-based systems for basic cell phones, and paper-based backup systems for communities without connectivity.^30

Low costs or Subsidized data packages specifically for Gradido transactions could accelerate adoption.^29

4. inclusion and distribution of power

Participatory processes can be dominated by certain groups if inclusion and diversity are not actively ensured. Specific mechanisms are necessary to ensure that:^59

Women have equal access and decision-making power

Marginalized groups (e.g. ethnic minorities, people with disabilities) are included

Younger and older generations both are represented

Rural and urban perspectives be balanced

The Valuation of contributions to the common good requires clear, consensual criteria to ensure fairness and acceptance.^44

5. prevent abuse and build trust

Transparent rules, robust governance structures and Sociocratic Circle Organization Method (SCM) can prevent abuse. Community-based moderation, as already practiced in Gradido Circles, allows for collective monitoring and mutual accountability - resonating with Fihavanana principles of community responsibility.^62

Corruption, which is widespread in Madagascar, must be addressed directly. Decentralized, open source-based systems with transparent transaction records can help prevent elite capture and build trust.^9^69

Networks and strategic partnerships

National partners:

Ministry of Digital Development, Post and Telecommunications (for digital infrastructure)^28

Ministry for Youth (for peacebuilding and community mobilization)^68

National Coordination for Inclusive Finance (CNFI) (for microfinance integration)^39

Madagascar Open Source Community (MOSC) (for technological development)^34

NGOs and civil society:

Money for Madagascar (Community savings groups, environmental protection)^38

SEED Madagascar (community health, education, women's lives, WASH)^65^61

Nofy i Androy (Girls' education)^17

Women Lead Movement Madagascar (Gender equality, leadership)^71

Akamasoa (poverty reduction, infrastructure)^60

Aga Khan Foundation/OSDRM (regenerative agriculture, microfinance)^27

International development organizations:

UNDP (Governance, Peacebuilding)^68

FAO (Dimitra Clubs, Agroecology)^5

World Bank/IFC (Private Sector Development)^6

Green Climate Fund (Climate-intelligent agriculture)^22

Technology and solar:

WeLight Madagascar (Solar Mini-Grids)^48

Barefoot College International (Women Solar Engineers)^63

Onja (Tech training, software engineering)^36

Passerelles Numériques Madagascar (Computer science training)^18

Madagascar as a model region for Africa

If Gradido pilot projects in Madagascar are successful, the country could become a Model region for profound transformation in Africa and beyond. The specific advantages would be:

Scientific evidence base: Enabling controlled pilots in geographically isolated communities rigorous impact evaluation - Comparison with control groups, longitudinal studies on poverty reduction, gender equality, environmental regeneration and social cohesion.^3

Replication blueprints: Documented learning processes, challenges and solutions from Madagascar can be customized implementation strategies for other African countries with similar contexts - high poverty, strong community traditions, digital transformation, climate vulnerability.^45

Pan-African Ubuntu Resonance: Fihavanana is not Madagascan in isolation, but part of a broader African Ubuntu philosophy, which is practiced from South Africa to Kenya, Malawi and Mozambique. A successful gradido model in Madagascar could be cultural acceptance in other Ubuntu-influenced societies.^10^73

South-South cooperation: Madagascar's experience could South-South knowledge exchange with other island states (Maldives, Marshall Islands, Philippines) or rural regions in Asia and Latin America that share similar challenges and potential.^58

Conclusion: Hope through community, innovation and appreciation

Madagascar is facing monumental challenges: 90 percent poverty rate, collapsing ecosystems, massive gender inequality, chronic underdevelopment. Nevertheless, signs of hope pervade the country - from Zanatany farmers, that double yields and protect forests, over Women solar engineers, that electrify villages, up to Self-help groups, achieve financial independence.^27^63

These initiatives show: Transformation is possible when community, initiative and innovative solutions come together. The Gradido model could act as a catalyst that:

Fihavanana values revived and modernized, by making community contributions economically visible and appreciated

Empowering women and girls through an active basic income for care work, education and leadership

Environmental regeneration financed via continuous cash inflows into the equalization and environmental fund

Digital innovation with open source principles and local expertise

Complementary to existing systems microfinance, VSLAs, mobile money - instead of replacing them

The path will not be easy. Cultural change, political resistance, technological hurdles, corruption and elite capture are real risks. But the Urgency of the crisis and the Strength of community traditions create a window of opportunity.

Madagascar could show that a another world is possible - one in which the economy serves life, not the other way around. One in which every person - whether a child or an old person, whether in Antananarivo or a remote village - is in Dignity, prosperity and harmony with nature can live. This vision is worth it, to collaborate, experiment and dream.

The signs are favorable. Now is the time to take the first step. <span style="“display:none“">^100^102^104^106^108^110^112^114^116^118^120^122^124^126^128^130^132^134^136^138^140^142^144^74^76^78^80^82^84^86^88^90^92^94^96^98</span>

<div align="“center“">⁂</div>

[^54]: https://www.grocentre.is/static/gro/publication/1767/document/Mialy Rakotondramboa.pdf

[^144]: https://www.measureevaluation.org/prh/research/best-country-fact-sheets/Urban-rural country fact sheet Madagascar.pdf