Pan-Africanism & Gradido

Homepage " Country research " Africa " Pan-Africanism

The content reflects the results of Perplexity's research and analysis and does not represent an expression of opinion by Gradido. They are intended to provide information and stimulate further discussion.

Pan-Africanism & Gradido - Opportunities for a self-determined, prosperity-oriented transformation of Africa

Summary of key findings

This research paper examines the historical development, current significance and future-oriented potential of Pan-Africanism in the context of a possible synergy with the Gradido model of the „Natural Economy of Life“. Pan-Africanism - as a historically evolved movement for unity, self-determination and liberation of all people of African descent - today faces the challenge of realizing economic sovereignty and sustainable prosperity for over 1.4 billion people. With its principles of the „triple bottom line“ (well-being of the individual, the community and the planet), debt-free money creation and the Active Basic Income, Gradido offers an innovative approach that harmonizes with the core objectives of Pan-Africanism.^1^3^5

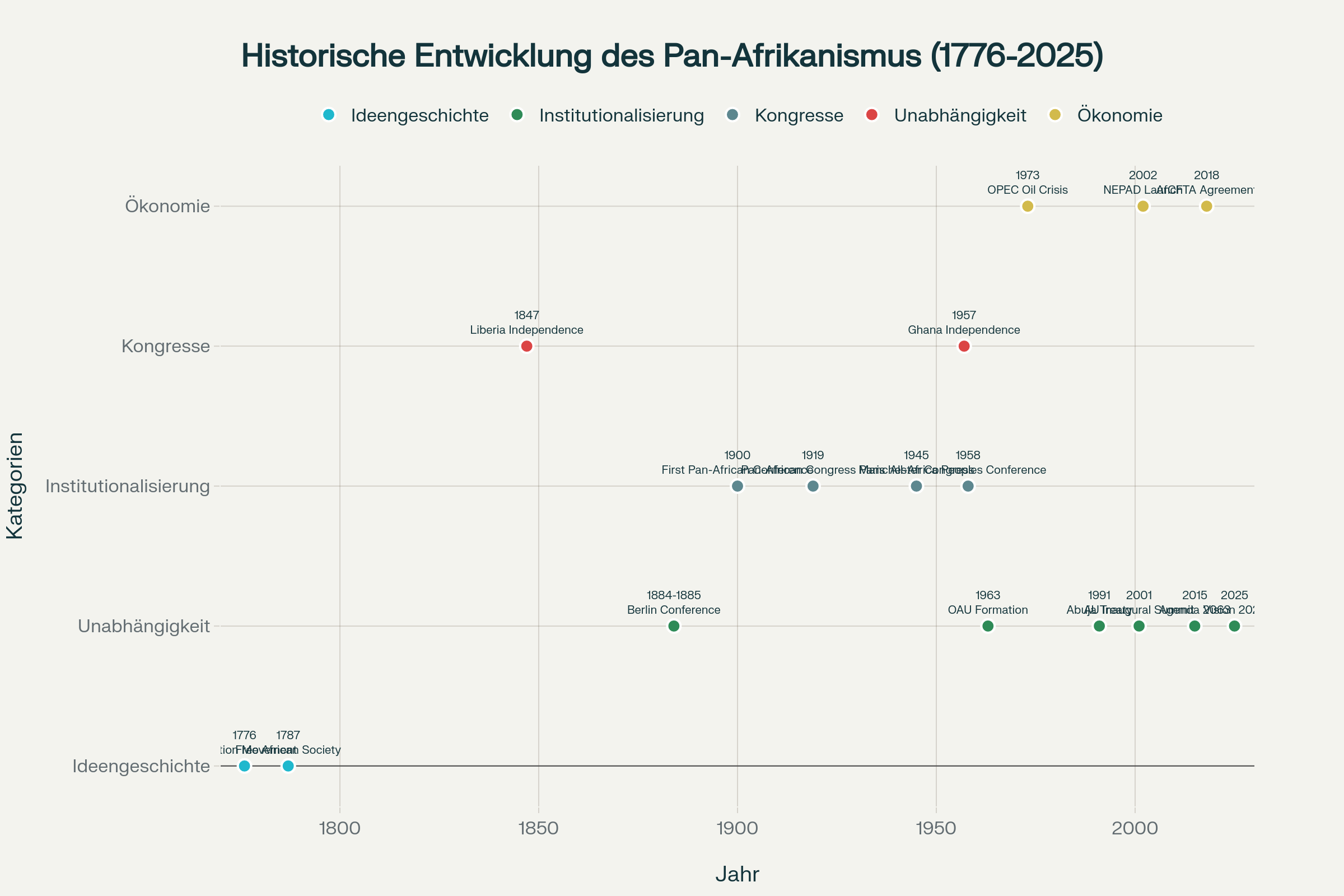

Timeline of the historical development of Pan-Africanism from its early intellectual beginnings to modern institutions and initiatives.

1 Concept, definition and basic principles of Pan-Africanism

1.1 What is Pan-Africanism?

Pan-Africanism refers to a political, philosophical, cultural and social movement that is committed to the Unity of all people of African descent worldwide - both on the African continent and in the global diaspora. The term was coined around 1900 by the Trinidadian lawyer Henry Sylvester Williams and developed into a comprehensive ideology that encompasses various dimensions.^6^8^10

At its core, Pan-Africanism is about the Overcoming the barriers created by slavery, colonialism and racism fragmentation and oppression of African peoples. The movement is based on the conviction that „African people, both on the continent and in the diaspora, share not only a common history but also a common destiny“.^11^13^15

1.2 Ethical and political foundations

The basic ethical values of Pan-Africanism:^11^10

Unity and solidarity: The idea of an overarching African identity that transcends ethnic and national boundaries Self-determination: The right of African peoples to determine their own political, economic and cultural paths Decolonization: Liberation from colonial structures - both physically and mentally Justice and equality: The fight against racism, discrimination and structural inequality Dignity and respect: The recognition and appreciation of African cultures, traditions and values

Political goals of Pan-Africanism:^17^19

Political independence of all African territories

Economic integration and self-sufficiency

Cultural renaissance and strengthening African self-confidence

Cooperation between African states and the diaspora

Eradication of poverty, exploitation and neo-colonial dependencies

1.3 Values for a just future

Pan-Africanism strives for:^13^15

Autonomy: Liberation from external dominance and control by former colonial powers or new forms of imperialism Prosperity for all: Overcoming extreme poverty and the unequal distribution of resources Peaceful coexistence: Ending conflicts and wars on the continent Ecological sustainability: Protecting Africa's natural resources from exploitation Cultural self-assertion: Pride in African identity, history and achievements

2. historical development of Pan-Africanism

2.1 Origins and early thinkers (18th-19th century)

The Roots of Pan-Africanism lie in the reaction to the transatlantic slave trade and colonial oppression. Early thinkers such as:^11^12

Martin Delany (1812-1885): US physician and activist who was one of the first to advocate the idea that people of African descent could not thrive alongside whites and advocated the return to Africa - „Africa for Africans“^14

Alexander Crummell (1819-1898): Believed that Africa was the best place for Africans and black Americans to create a united nation^14

Edward Wilmot Blyden (1832-1912): Considered one of the true „Fathers of Pan-Africanism“. The West Indian-born intellectual wrote about the potential of African nationalism and self-government in the face of growing European colonialism^21

James Africanus Beale HortonBlyden's contemporary, who also wrote about African nationalism and inspired the later generation^21

2.2 The Pan-African Congresses (1900-1945)

The Formal organization of Pan-Africanism began with the Pan-African Congresses:^13^17

1900 - First Pan-African Congress, London: Organized by Henry Sylvester Williams, this congress called for an end to discrimination and better living conditions for people of African descent^21^13

1919 - Second Congress, Paris: W.E.B. Du Bois, who is considered the „father of Pan-Africanism“, organized this congress parallel to the Paris Peace Conference. The participants demanded the right to self-determination for African peoples^14^13

1921-1927 - Further congresses: Further meetings were held in London, Brussels, Lisbon and New York, which kept the movement alive^8^13

1945 - Fifth Pan-African Congress, Manchester: This congress was decisive, as future African presidents such as Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya), Hastings Banda (Malawi) and Nnamdi Azikiwe (Nigeria) took part. The declaration called for the first time Immediate independence and Self-government for African colonies^17^13

2.3 Key people and their contributions

W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963): US-American sociologist, historian and activist. Organized several Pan-African congresses, founded the NAACP and intellectually developed the concept of Pan-Africanism. Emphasized the links between capitalism and racism^22^25

Marcus Garvey (1887-1940): Jamaican activist, founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and the Back-to-Africa movement. Popularized the slogan „Africa for Africans“ and promoted black economic nationalism. His ideas were controversial, but he mobilized millions^24^23

Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972): First president of independent Ghana (1957), visionary of the African political unity. Called for a „United Africa“ and was instrumental in the founding of the OAU (1963) was involved. Warned against Neocolonialism^13^26^25^20

Julius Nyerere (1922-1999): First President of Tanzania, theorist of the Ujamaa („familyhood“) - a form of the African socialism. Pursued economic self-sufficiency and pan-African solidarity, supported liberation movements in the region^26^29^31^32

Thomas Sankara (1949-1987): Revolutionary president of Burkina Faso, known for his radical anti-imperialist Politics, self-sufficiency and the fight against corruption. Embodied an uncompromising Pan-Africanism^27

Aimé Césaire (1913-2008) & Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906-2001): Founder of the Négritude movement, which promoted the cultural self-assertion of black people and rejected colonial inferiority^34^36^38

Frantz Fanon (1925-1961): Psychiatrist and philosopher, author of „Black Skin, White Masks“ and „The Wretched of the Earth“. Analyzed the psychological effects of colonialism and inspired liberation movements worldwide^35^34

2.4 The role of the diaspora

The African diaspora - especially in the USA, the Caribbean and Latin America - played a central role in the development of Pan-Africanism. Many of the early thinkers and activists came from the diaspora and brought their experiences of racism and discrimination to the movement.^21^7

The diaspora provided intellectual leadership, Financial support and political mobilization. Movements like Black Lives Matter (2020) showed that solidarity between Africans on the continent and in the diaspora is still alive today.^12

2.5 Historical milestones

1957: Ghana's independence under Nkrumah - a symbol of the possibility of liberation^13^25

1960: The „Year of Africa“ - 17 countries gained their independence^41

1963: Foundation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Addis Ababa by 30 African states^43^44^41

1967: Arusha Declaration by Julius Nyerere - Manifesto for Ujamaa and African socialism^28^32

1990: Namibian independence - end of formal colonial rule^41

1994: End of apartheid in South Africa^41

2002: The OAU becomes the African Union (AU) Transformed^42^45^43

3. ideological currents and related movements

3.1 Different strands of Pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is not a monolithic ideology, but rather encompasses various Currents:^7

Anglophone tradition: Strongly influenced by W.E.B. Du Bois, with a focus on political unity and intellectual activism. Dominant in West Africa (Ghana, Nigeria) and Anglophone countries^22

Francophone tradition: Characterized by the Négritude movement by Césaire and Senghor, with a focus on cultural identity and literary self-assertion^34^36^38

Lusophone tradition: In Portuguese-speaking countries (Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau), a militant Pan-Africanism developed in the context of protracted wars of liberation

3.2 Négritude

Négritude is a literary-philosophical A movement that emerged in Paris in the 1930s. Its main representatives were:^35^38

Aimé Césaire (Martinique): Invented the term „négritude“ and emphasized the acceptance of black identity as a Means of decolonizing the mind^34

Léopold Sédar Senghor (Senegal): Saw Négritude as the sum of the civilizational values of the black world, but also emphasized the synthesis with European culture^36^39

Léon-Gontran Damas (French Guiana): more radical representative, sharply criticized French assimilation^37

Négritude was a Counter-movement on European colonialism and racism, which the cultural self-assertion in the foreground.^39^37

Frantz Fanon criticized the Négritude as too essentialist and temporary. He saw it as a necessary but not sufficient phase of decolonization.^38^35

3.3 African Socialism and Ujamaa

African socialism was created as an experiment, Western socialist ideas with traditional African values to connect:^26

Ujamaa (Julius Nyerere): Means „familyhood“ in Swahili. Nyerere saw the traditional African village community as the basis for a non-Marxist socialism. Ujamaa rejected both capitalism (exploitation of man by man) and doctrinaire socialism (inevitable conflict)^28^30

Core principles: Freedom, equality, unity; cooperative production; self-sufficiency; democratic participation^30

Practical implementation: From 1968-1975, villages in Tanzania were collectivized (Operation Vijiji), often by force. Economically, Ujamaa was problematic, but it promoted literacy, health and social equality^30

Other forms of African socialism were developed by Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Léopold Senghor (Senegal), Sékou Touré (Guinea) and Tom Mboya (Kenya) are represented.^26

3.4 Black Power and the diaspora

Black Power was a movement in the USA in the 1960s that demanded black self-determination, pride and political power. It was strongly inspired by Pan-Africanism, particularly through Marcus Garvey.^14

Connections:

Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam emphasized African identity

The Black Panther Party had international solidarity in its program

Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture) moved to Guinea and became a direct pan-African activist

The Diaspora movements influenced African liberation struggles and vice versa. There was a transnational exchange of ideas, support and solidarity.^12^40

4. institutionalization and modern movements

4.1 Organization of African Unity (OAU, 1963-2002)

The OAU was published on May 25, 1963 was founded in Addis Ababa by 30 African states:^41^42^45

Objectives of the OAU Charter:

Promotion of the Unity and solidarity African countries

Coordination and intensification of the Cooperation for development

Defense of the Sovereignty and territorial integrity

Elimination of colonialism in Africa

Promotion of international cooperation

Achievements:

Creation of a Forums for African countries

Support from Liberation movements (African Liberation Committee)

Contribution to ending the Apartheid in South Africa

Mediation for regional conflicts

Problems and criticism:

Principle of Non-interference often prevented effective intervention in crises

Weak assertiveness of resolutions

Dominance of individual countries

4.2 African Union (AU, since 2002)

The AU was founded in 2002 as Successor organization of the OAU, with expanded competencies:^43^44^46

Structure:

Head office: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Members: 55 African countries (Morocco has been included again since 2017)^46

Pan-African Parliament: Headquarters in Midrand, South Africa^6

Goals of the AU:

Larger Unity and solidarity between African countries

Promotion of Democracy, good governance and Human rights

Promotion of Peace and security

Promotion of the sustainable development

African continental integration^47

New elements vis-à-vis the OAU:

Right of intervention for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity

African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA)

Stronger focus on Socio-economic integration^44

4.3 Agenda 2063: The vision for Africa

The Agenda 2063 is that strategic framework of the AU for Africa's socio-economic transformation over 50 years (2013-2063):^43^49^51^52^54^56

Vision: „An integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens and a dynamic force in the international arena“^56

Seven key objectives (aspirations):

Prosperity through sustainable growth and industrialization

Integration on a united African identity and free trade area

Good governance, democracy and human rights

Peace and security

Cultural renaissance, strengthening African values

Sustainable development and climate protection

Flagship projects:

African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)

High-speed train network between African capitals

AU passport and lifting of the visa requirement

Pan-African e-network (Digitization)

Single African Aviation Market (SAATM)

Implementation:

First ten-year phase (2013-2023): Focus on economic growth, integration, good governance

Second phase (2024-2033): Accelerating progress^55

Challenges:

Financing the projects

Political will of the member states

Ongoing conflicts and instability

Uneven development between regions^55

4.4 African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)

The AfCFTA is one of the most important flagship projects of Agenda 2063:^57^49^51^59

Key data:

Signature: March 2018

Entry into force: May 30, 2019

Start of trading: January 1, 2021

Goals:

Creation of a uniform market for goods and services

Facilitation of the Movement of persons and capital

Removal of trade barriers (Customs duties and non-tariff barriers)

Promotion of the Intra-Africa trade (currently only ~10-13%)^49^48

Promotion of the Industrialization and regional value chains^58^48

Potential:

Largest free trade zone since the founding of the WTO

Market with 1.4 billion people

Challenges:

Infrastructure gaps (transport, energy, digitalization)

Different levels of development of the member states

Overlapping memberships in regional economic communities

4.5 Regional economic communities

ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States):

Founded in 1975, 15 member states

Objectives: Economic integration, freedom of movement, common currency (planned: ECO)

Current crisis: Withdrawal of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger (AES alliance) in January 2025^60^62^64

SADC (Southern African Development Community):

16 members in southern Africa

Focus on economic integration and development

EAC (East African Community):

8 members (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, South Sudan, DR Congo, Somalia)

Ambitious integration process (customs union, common market, planned monetary union)^33

Problems:

Multiple memberships cause conflicts and inefficiencies

Different levels of integration

Political tensions between member states

4.6 Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS)

PAPSS is an initiative to create a pan-African payment system:^62^66

Goals:

De-dollarization of intra-African trade

Reduction of transaction costs (currently many payments have to go via Europe/USA)

Promotion of local currencies

Financial integration

Status: Pilot and expansion phase, gradual introduction in various countries^51

4.7 Alliance des États du Sahel (AES)

The AES is a newer one, sovereignty-oriented Alliance of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger (all under military governments):^60^63^65

Foundation: September 2023

Main objectives:

Security cooperation against terrorism

Economic cooperation

Sovereignty against external influences (especially France)

Measures:

Withdrawal from ECOWAS (January 2025)

Foundation of own 5000-strong armed forces

Interpretation:

Expression of a new Pan-Africanism, based on self-determination and rejection of Western dominance

Criticism: authoritarian regimes, danger of isolation, economic risks^63^60

4.8 Modern pan-African movements

Civil society and grassroots organizations:

#EndSARS (Nigeria): Protest against police violence inspired by Black Lives Matter^67

#ShutItAllDown (Namibia): Fight against gender-based violence^40

Democracy movements in various countries^67

Cultural renaissance:

Afrobeats, Afrofuturism and pan-African art

Growing self-confidence among young Africans

Use of social media for pan-African networking

Diaspora engagement:

Remittances (remittances) are an important source of income

Return of diaspora Africans („repats“) to Ghana, Rwanda, etc.

Investments by diaspora entrepreneurs^40

Intellectual Pan-Africanism:

Achille Mbembe (Cameroon/South Africa): Contemporary thinker, Holberg Prize winner, head of the Innovation for Democracy Foundation^67

New generations of African intellectuals continue to develop Pan-Africanism^68

5. pan-Africanism, economy and development

5.1 Economic reality of life in Africa

Africa faces enormous economic challenges:^69^71^72

Debt:

Africa's foreign debt has risen from USD 354 billion in 2009 to 1.14 trillion USD (2022) increased^73

Debt service accounts for over 10% of government expenditure (2009: 3%)^69

Almost half of African countries is in a debt crisis^71

Poverty and inequality:

Despite growth in some countries Extreme poverty widespread

Uneven distribution of resources and income

Youth unemployment is high^20

Dependence on raw material exports:

Many countries mainly export Raw materials (oil, minerals, agricultural products)

Low added value in the country

Balance of trade:

Africa's share of world trade: only ~3%^58

Intra-African trade: only 10-13% (in comparison: EU ~60%)^49

Dependence from Europe, China and the USA

5.2 Neocolonialism and currency dependency

Neocolonialism refers to the continuation of colonial exploitation through Economic and political control after formal independence:^18^70^72

Main mechanisms:

Resource extraction by multinational corporations

Unequal trade relations

Indebtedness and structural adjustment programs (SAPs)^76

5.3 The CFA franc: a symbol of neo-colonial dependence

The CFA franc is perhaps the most obvious form of neo-colonial control:^75^78^80^82

History:

Created 1945 by France for its colonies

Originally: „Franc des Colonies Françaises d'Afrique“

Today: „Franc de la Coopération Financière en Afrique“

Structure:

Two currency zones: West African (UEMOA, 8 countries) and Central African (CEMAC, 6 countries)^78^75

Pegging to the euro (formerly Franc français)

Guarantee by the French Treasury

Mechanisms of control:

Compulsory deposit: 50% of the foreign exchange reserves must be held in a French government account^77^78

French veto power in the central banks

Fixed exchange rate Prevents independent monetary policy

Criticism:

Prevents independent economic policy

Symbol of French dominance („Françafrique“)^79

Attempts at reform:

2019/2020: Announcement of the renaming to „ECO“ for West Africa

But: Euro peg remains in place

Pan-Africanist movements demand the complete abolition of the CFA franc.^75^80

5.4 Challenges for economic independence

Structural problems:

Infrastructure deficit: Inadequate roads, ports, energy^50

Educational gaps: Shortage of qualified workers

External constraints:

Global financial markets: High interest rates for African bonds^69^74

International financial institutions: IMF and World Bank often with restrictive conditions^70^76

Geopolitical competition: Rivalry between China, USA, EU, Russia for influence^20

Climate change:

Africa is particularly vulnerable against climate impacts

Droughts, floods threaten agriculture

High adaptation costs with low own emissions

5.5 Approaches to community-oriented, sustainable development models

Despite the challenges, there are Promising approaches:^20^85

Community-based development:

Microfinance and local savings banks

Cooperatives in agriculture

Social enterprise^86

Digital innovation:

M-Pesa (Kenya): Mobile payment system revolutionized financial inclusion^87^89

Leapfrogging: Skipping outdated technologies^90

Complementary currencies:

Sarafu (Kenya): Community currency on a blockchain basis^91

Eco-Pesa (Kenya): Environmental protection currency^86

Other local currencies in various countries^92

Ujamaa and cooperative models:

Despite failures in Tanzania: Principles remain relevant^28^30

Modern interpretations in Community projects

6. comparison & opportunities: Gradido as a pan-African economic model

6.1 Basic ethical values: Triple good and Pan-Africanism

The ethical principles from Gradido harmonize remarkably with the Goals of Pan-Africanism:^1^3^5

Gradido principle: Triple well-being

Well-being of the individual: Active basic income, dignity, development of potential^4^5

The good of the community: Public welfare contributions, public budget without taxes^5^95

Good for the earth: Equalization and environmental fund, sustainability^93^4

Pan-Africanism: Core values

Harmony with nature (traditional African understanding)^28

Parallelism:

Both emphasize Community-oriented values about individual profit

Both strive for Justice and overcoming exploitation

Both see Nature as a partner, not as a resource to be exploited

6.2 Economic sovereignty through Gradido

Gradido could have several Pan-African destinations address:^1^4^96^84

Overcoming debt:

Gradido becomes Created debt-free - No compulsion to take on new debt^3^5^1

Planned transience (50% per year) prevents accumulation^97^98^3

Exemption from Interest and compound interest mechanism^1^97

Monetary sovereignty:

Gradido could be used as complementary or alternative currencies exist alongside national currencies^99^100

Decentralized money creation through communities^101^100^102

Regional integration:

Common currency as a symbol of Unit^96

Poverty reduction:

6.3 Needs of the Pan-African Vision and Gradido responses

Need: Recognition of all people

Gradido response: Unconditional participation, everyone can contribute^4^5

Implementation: 20 GDD per hour for public welfare contributions, up to 1000 GDD/month^94^4

Need: lifting poverty

Gradido response: Active basic income as a systemic component^5^4

Effect: Securing a livelihood without debt, dignity instead of handouts^93^5

Need: Participation and democracy

Gradido response: Decentralized communities decide what counts as a contribution to the common good^104^5

Democracy: Use of the public budget is determined jointly^4^104

Need: Regional integration

PAPSS compatibility: Gradido could be integrated with pan-African payment systems^51

Need: Ecological sustainability

Gradido response: Compensation and environmental fund (1000 GDD per person/month)^95^93

Effect: Systematic financing of environmental protection and renaturation^5

6.4 Gradido as a decolonial tool

Decolonial perspective:

Breaking with the debt money system:

The current debt money system is Legacy of colonialism^70^72

Gradido offers Alternative without structural dependency^1^4

Local control:

Cultural fit:

Self-empowerment:

6.5 Compatibility with community banking and digital currencies

Community Banking:

Gradido can Decentralized be introduced in local communities^101^100^91

Integration with existing Microfinance and VSLA (Village Savings and Loan Associations)^92

Digital currencies:

Gradido uses Modern blockchain technology (4th generation DLT)^106^107

Mobile payment: Integration into existing systems such as M-Pesa possible^87^88

Offline capability: Can also be used by people without permanent Internet access^108

Cash alternative: DankBar:

Important for Africa: Many people do not have access to digital devices

Freedom: Guaranteed „coined freedom“ without digital surveillance^111

Example Sarafu (Kenya):

Community currency on blockchain, similar principles^91

During COVID-19: Transaction volume tenfold^91

Shows Potential for complementary currencies in Africa^86^91

6.6 Grassroots vs. top-down: synergy possible

Bottom-up approach:

Top-down support:

Regional organizations (ECOWAS, SADC) as multipliers^61

Synergetic approach:

Scientific support and evaluation

Political support follows proven successes

7. strategies, success factors & challenges

7.1 Success factors for public good-oriented currencies

Trust:

Network effects:

Practical benefits:

Technology:

7.2 Role of various stakeholders

African Union:

Political legitimacy for pan-African currency projects^43^51

Integration in Agenda 2063 and Digital Transformation Strategy^116^117

Regional mergers:

National governments:

Tax treatment clarify^108

Local communities:

Civil society & NGOs:

Private sector:

7.3 Regulatory, economic and technical hurdles

Regulatory hurdles:

Economic hurdles:

Initial skepticism from retailers and service providers^91^108

Exchange rate risks with complementarity^112

Competition to established systems^92

Technical hurdles:

Digital divide: Not everyone has smartphones or the internet^115^118

Energy supply: Power shortage in many regions^88

Cybersecurity risks^114

Cultural hurdles:

Educational deficits: Understanding new systems^115

7.4 Priority steps and pilot projects

Phase 1: Preparation and awareness-raising (6-12 months)

Phase 2: Pilot projects (1-2 years)

Various sectors: Care work, agriculture, education, health^5^108

Accompanying research: Quantitative and qualitative evaluation^91^108

Phase 3: Scaling (2-5 years)

Technological development^100

Phase 4: Institutionalization (5-10 years)

Recommended pilot regions:

Kenya: Experience with M-Pesa and Sarafu, innovative ecosystem^87^91

Ghana: Pan-African symbol, open government, diaspora engagement^13^25

Rwanda: Digital transformation, political stability^88

Senegal: Francophone region, Négritude tradition^35

South Africa: Developed economy, strong civil society^67

7.5 Partners and supporters

Strategic partners:

AUDA-NEPAD (African Union Development Agency)^51

African Development Bank (AfDB)^69

Smart Africa Alliance^116

Development partner:

Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (already supports conferences on African economic sovereignty)^74^120

GIZ (German Society for International Cooperation)^61

EU as part of the Digital4Development initiative^119

Technology partner:

Scientific partners:

8 Africa as a beacon of hope for global transformation

8.1 Impulses from pan-African visions and Gradido

Africa is at a historic turning point:^88^53^56

Demographic bonus:

Youngest population worldwide (median age: ~19 years)^53

By 2050: 2.5 billion people (28% of the world population)^53

Digital leapfrogging:

Mobile payment already further than in many industrialized countries^87

Resource wealth:

60% of uncultivated arable land Worldwide^56

30% of the world's minerals^56

Potential for renewable energies (solar, wind, water)^90

Cultural diversity and creativity:

Afrobeats, Nollywood, literature gain global influence^68

Afrofuturism as a cultural movement^68

Ubuntu philosophy as an alternative world view

8.2 Gradido and the vision of „prosperity and peace for all“

Gradido embodies a radical alternative to the status quo:^1^3^4

Prosperity for all:

Triple money creation Finances individual, society, nature^5^4

Plus-sum principle instead of a zero-sum game^124

Peace:

Harmony with nature:

Africa as a pioneer:

Reduced path dependency to old systems^88

8.3 Africa and the diaspora as trailblazers

Historical role of the diaspora:

Financial support (Remittances: billions annually)^103

Political pressure on international institutions^12

Modern networking:

Black Lives Matter showed global solidarity^40

Diaspora investments in African startups^88

Return movements („Year of Return“ in Ghana, etc.)^68

Shared vision:

Pan-Africanism 2.0: Digitally networked, global solidarity^67^68

Gradido as a joint project: Diaspora can support implementation^101

Knowledge transfer: Diaspora brings expertise, Africa brings implementation energy^88

8.4 New Earth: From Africa for the world

Africa as a model:

When Gradido in Africa Successful is a signal for other continents^1^101

Alternative to western development: Not a copy, but our own way^70^72^120

Global inspiration:

Transformation of the global financial system:

Vision 2063 and beyond:

Agenda 2063: Integrated, prosperous, peaceful Africa^52^54^56

Gradido 2063: Natural economy of life for the whole of Africa - and the world^2^5^4

Conclusion

Pan-Africanism and Gradido share a Shared visionThe creation of a just, solidary and sustainable world in which all people can live in dignity. The historical movement of Pan-Africanism has Liberation from colonialism - now the economic liberation to.^1^6^18^20^4^56

Gradido offers with its principles of Triple well-beingthe debt-free money creation and the Active basic income an innovative framework that harmonizes with the core objectives of Pan-Africanism. The Compatibility is not accidental, but is rooted in a common understanding of Community, justice and harmony with nature.^2^28^4^1

The Challenges are enormous: debt, neo-colonial structures, currency dependency, poverty, conflicts. But it is precisely these challenges that create the Urgency and openness for radical alternatives.^69^20^83

Africa is not at the end, but at the Beginning: With the youngest population, rapid digital transformation, cultural renaissance and pan-African institutions such as the AU and AfCFTA, the continent is ready for a Quantum leap.^88^53^56

Gradido could be the Catalyst be - not as an external solution, but as a Tool, that Africa can take into its own hands and adapt to its needs. From Grassroots communities in Kenya up to continental institutions in Addis Ababa - the potential is there.^43^51^4^93^56

The time is ripe. Pan-Africanism and Gradido together can pave the way for Prosperity and peace for all, in harmony with nature - not only for Africa, but for the whole Human family.^124^97^5^56^2

Africa as a beacon of hope, Gradido as an instrument, Pan-Africanism as a vision - Together they can new earth create.^97^5^67^1

Literature and sources

This research is based on a comprehensive analysis of over 100 academic, journalistic and institutional sources from 1900 to 2025, including historical documents on pan-African congresses, recent African Union reports, economic analyses of debt and monetary systems, and foundational texts on the Gradido model of the Natural Economy of Life. <span style="“display:none“">^127^129^131^133^135^137^139^141^143^145^147^149^151^153^155^157</span>

<div align="“center“">⁂</div>